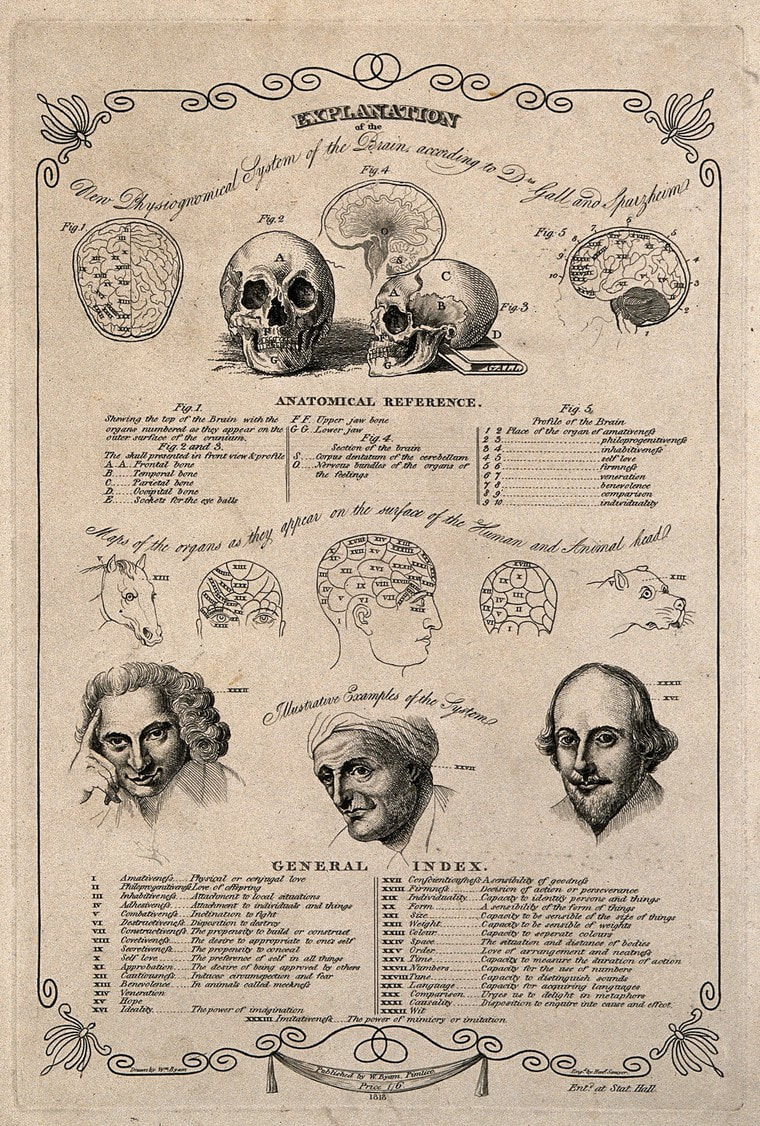

Phrenological diagrams of the skull and brain, with three portraits: Laurence Sterne [LEFT], a mathematician [MIDDLE], and Shakespeare [RIGHT]; exemplifying the faculties of wit, number and imagination respectively. Engraving by H. Sawyer after W. Byam, 1818. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

|

Phrenological diagrams of the skull and brain, with three portraits: Laurence Sterne [LEFT], a mathematician [MIDDLE], and Shakespeare [RIGHT]; exemplifying the faculties of wit, number and imagination respectively. Engraving by H. Sawyer after W. Byam, 1818. Credit: Wellcome Collection. CC BY

0 Comments

Here are some excerpts from Rilke's observations of Rodin published in this riveting small book (made available for free use online via Project Gutenberg). "For it was just that which Rodin was seeking: the grace of the great things."

"There were small figures, animals particularly ... All had transformed and accommodated themselves to this environment; they had lost nothing of life. On the contrary, they lived more strongly and more vehemently—lived forever the fervent and impetuous life of the time that had created them. And whosoever saw these figures felt that they were not born out of a whim nor out of a playful attempt to find forms unheard of before. Necessity had created them." "The language of this art was the body." "Here was a task as great as the world ... Here already Rodin's deep harmony with Nature revealed itself; that harmony which the poet George Rodenbach calls an elemental power ... He began with the seed beneath the earth, as it were. And this seed grew downward, sunk deep its roots and anchored them before it began to shoot upward in the form of a young sprout. This required time, time that lengthened into years. "One must not hurry," said Rodin to the few friends who gathered about him, in answer to their urgence." "His real development ... was compressed into the free hours of the evening and unfolded itself in the solitary stillness of the nights; and he had to bear this division of his energy for years. He possessed the quiet perseverance of men who are necessary, the strength of those for whom a great work is waiting." "Rodin knew that, first of all, sculpture depended upon an infallible knowledge of the human body ... it was this surface toward which his search was directed. It consisted of infinitely many movements. The play of light upon these surfaces made manifest that each of these movements was different and each significant ... There were undulations without end. There was no point at which there was not life and movement." "Rodin had now discovered the fundamental element of his art; as it were, the germ of his world. It was the surface,—this differently great surface, variedly accentuated, accurately measured, out of which everything must rise,—which was from this moment the subject matter of his art, the thing for which he laboured, for which he suffered and for which he was awake. His art was not built upon a great idea, but upon a minute, conscientious realization, upon the attainable, upon a craft." "The next task was to become master of himself and of his abundance. Rodin seized upon the life that was everywhere about him. He grasped it in its smallest details; he observed it and it followed him; he awaited it at the cross-roads where it lingered; he overtook it as it ran before him, and he found it in all places equally great, equally powerful and overwhelming. There was not one part of the human body that was insignificant or unimportant: it was alive." "For years Rodin walked the roads of life searchingly and humbly as one who felt himself a beginner. No one knew of his struggles; he had no confidants and few friends. Behind the work that provided him with necessities his growing work hid itself awaiting its time. He read a great deal." "Rodin dwelt in the books of the poets and gleaned from the past. Later, when as a creator he again touched those realms, their forms rose like memories in his own life, aching and real, and entered into his work as though into a home." "Only his work spoke to him. It spoke to him in the morning when he awakened, and at even it sounded in his hands like an instrument that has been laid away. Hence his work was so invincible. For it came to the world ripe, it did not appear as something unfinished that begged for justification. It came as a reality that had wrought itself into existence, a reality which is, which one must acknowledge." "Rodin's conception of Art was not to beautify or to give a characteristic expression, but to separate the lasting from the transitory, to sit in judgment, to be just." "To Rodin the participation of the atmosphere in the composition has always been of greatest importance. He has adapted all his figures, surface after surface, to their particular space and environment; this gives them the greatness and independence, the marvelous completeness and life which distinguishes them from all other works. When interpreting nature he found, as he intensified an expression, that, at the same time, he enhanced the relationship of the atmosphere to his work to such a degree that the surrounding air seemed to give more life, more passion, as it were, to the embraced surfaces." "... he worked incessantly; his life passed like a single working day." "He was a worker whose only desire was to penetrate with all his forces into the humble and difficult significance of his tools. Therein lay a certain renunciation of Life, but in just this renunciation lay his triumph, for Life entered into his work." |

This is ...

an entirely unstructured & zany exploration of all things that are or could be relevant to understanding the human imagination. Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed